A thesis submitted to the Dublin Institute of Technology in part fulfilment of

the requirements for the award of Masters Degree (M.A.) in Criminology

By

Paul Williams

September 2016

Supervisor: Dr. Matt Bowden

Supervisor: Dr. Matt Bowden

Declaration

I hereby declare that the material which is submitted in this thesis, towards the award

of the Masters (M.A.) in Criminology, is entirely my own work and has not been

submitted for any academic assessment other than part fulfilment of the award named

above

Signature of Candidate _____________________________

(Paul Williams).

Date ____________________

Abstract

The unofficial, internal culture of An Garda Siochana is an area where there has been a deficit of academic research and scrutiny despite it being existential to the public discourse on garda reform, especially in recent years. It has been pointed out that the lack of data on the organisational value system of the Irish police is due in part to the nascent state of criminological research in Ireland and a reluctance on the part of the Garda authorities to cooperate in research studies. The primary objective of this study was to explore one aspect of police culture: the impact of working in a confrontational and conflicted environment on individual frontline gardai as seen through the lens of their lived experiences. The responses of the research participants were then analysed and considered in the context of the existing theoretical framework of police occupational culture. A qualitative approach was adopted using the format of semi-structured interviews in order to allow the interviewees greater flexibility and scope in expressing their experiences and perceptions. The data sample group consisted of eight serving members which was evenly divided between gender, rank (garda or sergeant) and geographical location (Northern and Southern Divisions of the Dublin Metropolitan Region). When the data were analysed a number of common cultural themes emerged from the responses of the individual participants which conflated with some of the main characteristics of police culture as identified in the literature including: social isolation/solidarity; ‘gallows humour’ as a coping mechanism for dealing with the stresses of the job; suspiciousness/wariness; cynicism; a desire for action; and an ‘us versus them’ division of the social world.

The principle conclusion of the research is that police culture in An Garda Siochana is formed by the experiences of young officers working in a confrontational environment. It also supports the theory that police forces in modern liberal, capitalist democracies, which face similar societal tensions, also share a range of distinctive cultural characteristics which are universal, stable and lasting. The primary recommendation is that much more comprehensive and expansive research is required in order to gain a greater understanding of the multidimensional occupational culture of the Irish police. Such detailed investigation is capable of providing invaluable and more enlightened insights for policy makers and stakeholders involved in the criminal justice sector.

Acknowledgement

My sincerest thanks to my supervisor, Dr. Matt Bowden, for his patience, guidance, encouragement and invaluable insights, and without whom I could not have completed this study.

I would also like to express my thanks and admiration to Dr Bowden’s colleagues on the academic staff on the MA Criminology for a thoroughly enjoyable and academically enriching experience at DIT Grangegorman over the past two years. Thanks also to the library staff who were always so helpful and obliging.

I want also like to express my gratitude to the staff of the Garda Research Unit who approved of my research application and organized access to the sample group.

And last, but not least, to the research participants who generously gave of their time and their honestly held views and insights.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Declaration

Abstract

Acknowledgment

Table of Contents

Chapter One. Introduction

1.1 Theoretical context of the study

1.2 Rationale for the research

1.3 Aims and objectives of the study

1.4 Organization of chapters

Chapter Two. Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

2.2 Defining the Police: the role and powers of frontline officers

2.3 The development of police occupational culture theory

2.4 The ‘working personality’ of the frontline police officer

2.4.1 Discretion 1

2.5 Occupational culture in An Garda Siochana.

2.6 Conclusion

Chapter Three. Methodology

3.1 Introduction

3.2 Aims and Objectives, Research Question

3.2.1 Issues addressed by the research

3.3 Research Design

3.3.1 Reflective note

3.4 Access, Data sample and Data collection process

3.4.1 Access

3.4.2 Data sample

3.4.3 Data collection

3.5 Ethical issues

3.6 Data analysis

3.7 Contribution of the study

3.8 Limitations of the study

3.9 Conclusion

Chapter Four. Findings

4.1 Introduction and key themes

4.2 Confrontation

4.3 Social Isolation/Internal Solidarity

4.3.1 Internal Solidarity

4.4 Cynicism: Street Cop Culture versus Managerial Culture

4.5 Suspicion: ‘Symbolic assailants’

4.6 Discretion

4.6.1 Peace-keeping/avoiding confrontation

4.6.2 Giving offenders a chance

4.7 Canteen culture

4.8 Action versus Social Service

4.9 Findings summary

Chapter Five. Discussion/recommendations

5.1 Conclusions

5.2 Recommendations

Bibliography/References

Appendices

Chapter One

1. Introduction

1.1 Theoretical context of the study.

A recurring theme within occupational sociology is that workers in diverse occupations develop distinctive ways of perceiving and responding to their environment. An occupational culture is a means for coping with the ‘vicissitudes or uncertainties arising routinely in the course of doing a job’ and provides a context ‘within which emotions are regulated and attuned to work routines’ (Manning, 2007: 865).

Police culture was first conceptualized from early ethnographic studies of routine police work which uncovered a layer of shared informal occupational values and norms operating under a rigid hierarchical organizational structure. Generally invoked by academics as condemnatory rather than explanatory, police occupational culture and sub-cultures are often portrayed as a ‘pervasive, malign and potent’ influence on contemporary policing, particularly in the lower ranks (Waddington, 1999: 287).

It derives from the discovery that the working practices of the police are far removed from legal precepts, and that officers exercise extensive discretion in how they enforce the law in their encounters with the public in conditions of ‘low visibility’ (Goldstein, 1960). Much of the theory suggests that the use of discretion by frontline police officers is influenced by a distinctive culture based on a shared informal belief system. The confrontational nature of modern police work has been identified as one of the factors underpinning police culture and that it lies in the early experiences of ‘rookies’ on patrol and the influence of peers (Goldstein, 1960; Banton, 1964; Skolnick, 1966; Westley, 1970; Holdaway, 1983; Goldsmith, 1990; Chan, 1996; Waddington, 1999; Reiner, 2010).

Yet, despite dominating criminological discourse since the 1960’s, the concept remains amorphous and difficult to define with more recent analysis suggesting that police culture is not primarily negative and that it has been ‘poorly defined’ and ‘of little analytic value’ (Chan, 1996: 110-111).

Robert Reiner (2010) describes how cop culture offers a patterned set of understandings that help officers cope with the uniquely dangerous and unpredictable nature of frontline police work. Elements of the police milieu, including danger, authority, conflict and confrontation, combine to generate distinctive cognitive and behavioral responses in police officers that Jerome Skolnick (1966; 2009) characterizes as the ‘working personality’ which ‘is most highly developed in his constabulary role of the man on the beat’ (2009: 580).

This research project focuses on one aspect of police culture: the impact of conflict and confrontation on frontline police through the lens of the lived experiences of individual gardai.

1.2 Rationale for the research.

The study of criminology and policing in particular, is a relatively nascent academic pursuit in Ireland which has been aptly described as the country’s ‘absentee discipline’ in Crime, Punishment and the Search for Order in Ireland (Kilcommins, O’Donnell, O’Sullivan & Vaughan, 2004). Prior to the book’s publication an academic infrastructure did not exist to sustain and promote empirical criminological research in Ireland, and consequently there was a paucity of data relating to the operational sectors of the criminal process, including the police (Maruna, 2007).

In Policing Twentieth Century Ireland: A History of An Garda Síochána (2014) Vicky Conway reveals that the lack of data concerning the organizational value system of the gardai is due in part to the nascent state of criminology and an ‘unwillingness on the part of the police to engage in such research’. She notes: ‘Data of this type could provide an innovative understanding of policing in Ireland, of prevalent cultures, of how social changes have changed the nature of policing, and of the lived experience of policing’ (Conway, 2014: 5 – 6).

In an effort to bridge the data gap Conway included oral history interviews with 42 retired gardai – 41 men and one woman – who provided frank testimonies of their service experiences in the period 1952 – 2006. She adopted this methodology because ‘access to serving gardaí is very difficult to secure (indeed, this researcher is unaware of any study of serving gardaí by someone external to the organisation)’ (2014: 219). Issues relating to police culture in Ireland became central to the public discourse regarding garda reform following a series of controversies that engulfed the justice sector in 2013/2014.

This research study is grounded in the lack of research of occupational police culture in Ireland. The project was made possible after the researcher gained access to a purposive sample of eight serving frontline members which was evenly divided between ranks – sergeant and garda – genders and frontline units.

1.3 Aims and objectives of the study.

The aim of the study is to explore the impact of working in a confrontational and conflicted environment on individual frontline gardai through the lens of their lived experiences; and the responses are analyzed to see if they are absorbed into the wider occupational culture of An Garda Siochana when considered within the existing theoretical framework.

The objective of the research is to provide a starting point for further research of police culture in Ireland which, despite being existential to the discourse regarding garda reform, remains largely uncharted territory.

The research design utilized a qualitative approach to the collection of data using the format of semi-structured interviews which allowed the interviewees greater flexibility and scope to express their views. This approach produced rich data with participants articulating several common themes contained within the theoretical characteristics of the police officer’s working personality.

1.4 Organization of Chapters.

There are five chapters in this dissertation including the Introduction. Chapter Two contains a review of a cross-section of the voluminous international literature on police occupational culture by firstly, defining the role and powers of the public police; and secondly, charting the evolution of policing scholarship in this area since the 1960’s. The Literature Review will also assess the existing (albeit sparse) relevant literature relating to the occupational culture of An Garda Siochana.

Chapter Three outlines and explains the research design and methodology employed in the study. It will discuss the rationale for the research topic; explain the process by which the sample group was selected; and how the data was collected, coded and then analyzed. The chapter will also address the ethical issues involved as well as the possible contributions and limitations of the study.

In Chapter Four the aim is two-fold: (i) to present the research findings; and (ii) to integrate the findings by discussing them in the context of the literature. Chapter Five concludes the thesis with a general discussion of the main findings followed by the recommendations.

Chapter Two

2. Literature Review

2.1 Introduction.

This chapter evaluates the main characteristics of police occupational culture within the existing theoretical framework. In order to contextualise the research the first section of the chapter defines the purpose, role and powers of the public police. The second section contains a description of the genesis and evolution of police scholarship over the past fifty years. It is then followed by a section highlighting the dominant themes of police culture, including an examination of the concept of discretion which is central to any discourse surrounding ‘street cop culture’. The final part of the chapter reviews existing literature within the context of the occupational culture of An Garda Siochana. The chapter ends with a conclusion and overview of the material discussed.

2.2 Defining the Police: the role and powers of frontline officers.

The police are identified primarily ‘as a body of people patrolling public places in blue uniforms, with a broad mandate of crime control, order maintenance and some negotiable social service functions. Anyone living in a modern society has this intuitive notion of what the police are’ (Reiner, 2010:3). The formal state police organization is the one agency of the state that every citizen feels they are familiar with and will have encountered at some stage in their daily lives. One of the fundamental deterrent roles of the police is that they are one of the ‘most visible and recognizable institutions in modern society’ (Newburn, 2007:598).

Whilst the establishment of formalised state policing arrangements is a historically recent development – coinciding with the establishment of Robert Peel’s London Metropolitan Police in 1829 – its dominant role in contemporary society and popular culture is such that the shared public assumption is that the police have always existed. The public’s obsession with ‘crime, flashing blue lights and wailing sirens’ has made the police ubiquitous in contemporary popular culture, dominating the 24/7 news and entertainment schedules (Emsley, 1991; Ignatieff, 1979; McLaughlin, 2007; Reiner, 2010; Zedner, 2004). The consequence of this cultural omnipresence, Reiner argues, is that modern societies are characterised by ‘police fetishism’ – the ideological assumption that police are a functional prerequisite of social order and all that stands between chaos and anarchy in ‘an uncontrolled war of all against all’ (Reiner, 2003: 259; 2007: 912).

The defining feature of the public police is as the sole institution through which the state ‘claims monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory…to the extent to which the state permits it. The state is considered the sole source of the right to use violence’ (Weber 1948:78, emphasis in original). The description of the police as officers of the law acknowledges their exclusive, non-negotiable right to exercise a range of coercive powers which supersede an individual’s civil rights, permitting them to search citizens and their property, monitor their movements and deprive them of their liberty. This power is utilized to perform their function of protecting the viability of the state and the security of its citizens – preventing crime, catching offenders and keeping the public peace (Conway, 2010; Loader & Mulcahy, 2003; Zedner, 2004).

The public police are ‘the most prominent and, arguably, the most powerful actors’ in the criminal justice system (Zedner, 2004:126) and are ‘housed within a specialist, hierarchical, bureaucratic institution whose members are set apart from ‘civilians’ by dint of their uniform, training, and an internal regime of vertical command structures and disciplinary rules and procedures’ (Loader & Mulcahy, 2003:41).

Robert Reiner describes policing as possessing a perpetual ‘Janus face’ (2010: 17) as it deals with conflict; inevitably helping some by controlling others. ‘One side’s reasonable and necessary force is the other’s unjust tyranny’ (ibid: xiii). A constant feature of the occupational culture of the police is coping with violence, or the threat of violence, that hangs over every working day. The police are distinct from other hazardous occupations – where there is a more calculable risk – because officers must confront situations that arise in emergencies where the risk of conflict lies in the uniquely dangerous, unpredictable outcome of encounters with the public (Crank, 2004; Waddington & Wright, 2008; Waddington, 1999).

Formal police organizations are inevitably associated with social complexity and inequality in a rapidly changing society, and within that context the purpose, conduct and efficacy of the police is a constant source of conflict, debate and controversy.

‘Danger is linked to authority, which is inherently part of the police milieu…it is because they represent authority that police officers face danger from those recalcitrant to its exercise’ (Reiner, 2010:119).

In observance of its core objective to protect and serve society the police perform a bewildering miscellany of public service tasks and interventions: traffic control, crime prevention and investigation, social service, order maintenance, public safety, counter-terrorism, the enforcement of Government policies, court orders and injunctions. The one feature that unifies most policing tasks, is that they generally arise in emergencies with the potential of conflict and confrontation, and involve ‘something that ought not to be happening and about which someone had better do something now!’(Bittner, 1974:30, emphasis in original).

Using empirical research data collected over a four year period from 28 police forces in five countries – UK, Canada, the USA, Japan and Australia – David Bayley (1994; 2009) discovered that frontline police spend the vast majority of their time sorting out problems rather than resorting to their bottom line power to make arrests. He summarized patrol work as being determined ‘almost entirely’ by what the public ask the police to do and that:

‘…contrary to what most people think, the police do not enforce their own conception of order on an unwilling populace…Police interrupt and pacify situations of potential or ongoing conflict…they rarely make arrests, though the threat of doing so always exists’ (Bayley, 2009:575)

The research also confirmed that as little as between seven and ten per cent of police call-outs actually involve crime while the rest can be categorised as calls from people with no one else to turn to. In most cases what is initially reported as a crime to the police often turns out not to be a crime. A regular call-out scenario involved lonely, elderly people reporting burglaries in progress so that the police would come and talk to them for a while. The multitude of diverse encounters inevitably involve society’s most vulnerable elements.

‘By and large the people police deal with are life’s refugees. Uneducated, poor, often unemployed, they are both victims and victimisers. Hapless, befuddled, beaten by circumstances, people like these turn to the police for help they can’t give themselves. There is little the police can do for them except listen, shrug and move on’ (Bayley, 2009:575).

Other international research generally supports the findings that frontline policing mainly involves mundane, non-crime related work which Felson (2002) eloquently summarised: ‘Police work consists of hour upon hour of boredom, interrupted by moments of sheer terror. Some police officers have to wait years for these moments’ (2002: 4). Manning describes how officers work the streets waiting for something to happen. ‘Boredom, risk and excitement oscillate unpredictably’ (2007: 866).

Bittner (1984) defines the experiences of frontline police officers as:

‘…essentially a sequence of adventurous encounters with evil by individual officers or pairs of officers, who are for the most part left to depend on their own strength, courage, and wit in critical situations, interrupted by stretches of banality and boredom’ (1984: 212)

In the vast majority of their diverse interactions with the public the police do not invoke their legal powers, opting instead to exercise their extensive discretionary powers to restore calm and order in their primary role as ‘peace keepers’ or ‘peace officers’. Successful policing requires pragmatism over legal zeal, utilizing the craft of handling trouble without resorting to coercion, most usually by the use of skilful verbal tactics. But underlying all of their difficult and challenging interactions with the public is the police officer’s bottom line power to wield legal sanctions and legitimate force (Banton, 1964; Skolnick, 1966, 2008, 2009; Holdaway, 1983; Bayley, 1994; Chan, 1996; Reiner, 1996, 2003, 2007, 2010; Waddington, 1999; Zedner, 2004).

2.3 The development of police occupational culture theory.

The empirical study of the social, psychological and cultural dimensions of policing was largely inspired by the sociological studies of Michael Banton’s The Policeman in the Community (1964) in the UK; and William Westley’s Violence and the police: A sociological study of law, custom and morality (1952; 1970) in the USA1 . Their work represented a breakthrough in post-war police scholarship as the first sociological studies of Anglo-American policing and made a convincing case for why the police should be a legitimate research topic for social scientific research (McLaughlin, 2007).

1 Westley came to policing through the lens of cultural interpretation, breaking new ground by moving from the traditional narratives of what the police do, to who they are, with particular emphasis on interpretations of how culture frames behavior. He conducted his research for a doctoral thesis in 1952 which was later published in 1970 (McLaughlin, 2007).

Westley discovered that as an occupational group the police possessed distinctive group customs, attitudes, values and modes of socialisation that influenced their actions. He wrote of how the constant exposure to corruption, immorality and degradation while working in a vortex of ‘anxiety, excitement, fear, and perhaps of madness’ drove police officers to band together, withdraw from the community, build a wall of secrecy, and live by their own rules (Westley, 1970).

Police studies marked a departure from the traditional positivist ‘science of criminology’, which had chosen to exclude the functioning of the police and criminal justice from its intellectual province, prompting new critical criminologies in the 1960s and 70’s that began to see as problematic the structure and functioning of criminal justice agencies, particularly the police.

The epistemological break coincided with the socio-economic, cultural and political transformations that convulsed Western democracies in the 1960’s, precipitating the collapse of the post-war consensual social order bringing an end to an age of deference and conformity in a process of ‘de-subordination’ (McLaughlin, 2007). The process of change widened the gulf between the police and the community, particularly the younger generation who began to express their independence by joining gangs like the mods and rockers.

Dramatic changes in patrolling methods, characterised by the introduction of squad cars and personal radios, rapidly reduced the number of officers on foot patrol which had been the traditional basis for positive social interaction with the public. The new policing philosophy favoured fast cars which transformed it into a glorified fire brigade service where officers patrolled the streets looking for action (Reiner, 2010). Loader and Mulcahy (2003) describe how this change in relationships between the police and the public provided a fertile ground for new studies of police culture because the ‘processes of detraditionalisation have come to have effects, not only upon the social world that the police are tasked with regulating, but also within the police organization itself’ (2003: 182, original emphasis).

This turbulent period also marked the reputational transformation of the British police from the ‘sacred’ phase, as evoked in Michael Banton’s sociological studies (1964) where the police were perceived as totems of moral superiority; to becoming a ‘profane’ institution following a process of de-sacralisation precipitated by corruption scandals, malpractice cases and allegations of racial discrimination.2 Reiner (1992a) suggests that the ‘sacred’ view characterised the ‘consensus’ stage in police research and marked the first of four distinguishable stages that have taken place since: ‘consensus’, ‘controversy’, ‘conflict’ and ‘contradiction’.

The socio-political and economic paradigm shift between the 1960s and 1980’s increased the level of conflict between the police and the public providing yet more fertile ground for academic research. In Britain and the USA the shift to neo-liberal, free-market economic policies – ‘capitalism unleashed’ – under the Governments of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, precipitated long-term unemployment, social exclusion and inequality whilst expanding a culture of consumer aspirations. The net effect was the unravelling of the traditional processes of social order and increased levels of crime. It also caused the politicisation of crime issues resulting in a shift from ‘penal welfarism’ to the ‘crime complex’ which favours incarceration over rehabilitation. The universal adoption of the neo-liberal agenda also ushered in a new concept of plural policing where the public police is located within a much broader framework of policing involving diverse networks and actors, and the privatisation of core justice functions (Holdaway, 1983; Chan, 1996; Morgan & Newburn, 1997; Garland, 2001; Loader & Mulcahy, 2003; Zedner, 2004; Jones & Newburn, 2006; McLaughlin, 2007; Mawby, 2008; Newburn, 2013; Newburn & Reiner, 2007; Reiner, 2010).

2 Banton first evoked the sacred status of the British police officer within a consensual social order. The sacralisation of the police officer as a moral agent derives from Durkheim’s concept of the existence of a structured power acting as an external constraint over the individual, who is above corruption and conscious about the power he wields for the good of the community. Banton defined the socially sacred as ‘that which is set apart and that which is treated both as intrinsically good and dangerous’ (Banton, 1964: p. 237)

2.4 The ‘working personality’ of the frontline police officer

Studies of police culture have generally fallen into two competing camps: the traditional characterization of an undifferentiated, monolithic, ‘one size fits all’ culture; compared to more recent theories recognizing that police culture is a much more diverse, fluid and changeable phenomenon containing multiple cultures and subcultures associated with differing types of police activity, specialization and managerial ranks in conjunction with the diversification of functions within plural policing. Police organisations develop their own distinctive cultural identity and it is within this structure that multiple cultures and sub-cultures emerge.

Cultures are influenced by organizational distinctions and variables based on multiple factors such as, for example, geography – urban versus rural; hierarchical divisions – the two-tiered option of management cops versus street cops, or the triple-layered one comprising command, middle-management and the lower echelons; distinctions within the lower ranks – detective versus street cop, or street cop versus community policing officer; distinctions within specialized groups – SWAT team members versus traffic cops. Other variables include differences of outlook within police organisations according to individual variables of personality, gender, ethnicity, sexuality, generation and career trajectory (Skolnick, 1966; Holdaway, 1983; Fielding, 1988; Chan, 1996, 1997; Waddington, 1999, 2008; Loader & Mulcahy, 2003; Manning, 1977, 2007; Paoline, 2004; Westmarland, 2008; Reiner 1992a; 2010).

Manning, (2007) defines an occupational culture as:

‘…a reduced, selective, and tank-based version of culture that includes history and traditions, etiquette and routines, rules, principles and practices that serve to buffer practitioners from contacts with the public. A kind of lens on the world, it highlights some aspects of the social and physical environment and omits or minimizes others. It generates stories, lore and legends’ (Manning, 2007: 865).

Jerome Skolnick’s classic formulation of the policeman’s ‘working personality’ (1966), which has been central to the discussions on the core police culture, outlines a number of environmental factors that influence the occupational culture. He synthesised earlier sociological research with his own findings to construct a pioneering sketch which referred not to an individual psychological phenomenon but a socially generated culture.

‘Police have a discernable culture flowing from the nature of the job, police behavior is strongly influenced by the underlying values – and politics – of the community that finances the police department (Skolnick, 2008: 39, original emphasis).

This culture emerges in response to a unique combination of facets of the police role: ‘Two principal variables, danger and authority, which should be interpreted in the light of a constant pressure to appear efficient’ (Skolnick, 1966:44). As the visible embodiment of social authority, police are exposed to danger and in order to cope with these pressures a set of informal rules, rites and recipes evolved and developed.

Skolnick identified suspiciousness as one of three dominant themes within cop culture because, as a consequence of the continuous preoccupation with potential violence and conflict, the front line officer develops a ‘perceptual shorthand’ to identify certain kinds of people as ‘symbolic assailants’. ‘This was an important observation because what officers identify as suspicious people, places, or circumstances determines who gets observed, scrutinized and interrogated by the police’ (Stroshine, Alpert & Dunham, 2008:315). Other features explained by Skolnick were internal solidarity, coupled with social isolation and conservatism. Suspiciousness renders the officer prone to operate with prejudiced stereotypes while the internal solidarity is created by the shared intense experience of confronting danger and the need to rely on colleagues. The multifarious interactions between the police officer and the public, dealing with violent people or enforcing the road traffic laws – ‘danger and authority’ – combined with the unsociable nature of the job, and a wariness of management, create the conditions of social isolation. Solidarity can also provide a defensive shield for wrong doing while isolation exacerbates prejudices.

When officers divide the world into we-versus-them, the former consists of other police officers while the latter encompasses almost everybody else. Skolnick argues that while members of other occupational groups also develop their own subcultures and worldviews, it is not to the same extent as the police. ‘Set apart from the conventional world, the policeman experiences an exceptionally strong tendency to find his social identity within his occupational milieu’ (Skolnick, 1966:52). Bayley’s research found that police tend to become cynical and suspicious as a consequence of their interactions with the public who ‘lie brazenly’ or ‘tell self-serving, partially true stories’ (2009:574).

According to Zedner (2004) the distinctive characteristics of street cop culture derive from the fact that police work closely together, in dangerous, unpredictable situations and often in conflict with the surrounding community. This engenders an institutionalized sense of isolation and an ‘us-and-them’ attitude to the world outside the police station. It is rooted in a shared knowledge system containing strongly-held beliefs about the nature of policing and those they police.

While culture is generally viewed negatively in police studies Westmarland argues that many commentators allude and yet do not explain or explore it in depth. ‘It is as if culture exists in the background of most discussions of policing and yet only comes to the fore when some misdemeanor or difficulty arises as a cover all explanation or excuse’ (Westmarland, 2008: 253).

Chan described the concept of police culture as a ‘convenient label for a range of negative values, attitudes and practice norms among police officers’ (1996:110). Waddington argues that the convenience lies in its ‘condemnatory potential: the police are to blame for the injustices perpetrated in the name of the criminal justice system’ (1999:293, emphasis in original).

Chan contends that police culture does not exist in a vacuum or is freestanding, but exists for a purpose. It can be viewed as functional to the survival of police officers in an occupation that is dangerous, unpredictable and alienating. The bond of solidarity is a form of reassurance that fellow officers will be there to defend and back up their colleagues when confronted by external threats (Chan, 1996, 1997).

The subcultural concept of ‘canteen culture’, which is also held up as a negative influence on police culture, is yet another tributary branching out from the crowded theoretical milieu. It refers to a system of values and beliefs – gallows humour – expressed by officers while socializing for the purpose of tension release (Reiner, 2010). Waddington (1999) concludes that what is spoken in the canteen or social environment is ‘expressive talk designed to give purpose and meaning to inherently problematic occupational experience’ (1999:287). Paoline (2004) also suggests that changes in the policing profession over recent decades with the recruitment of more females, racial minorities and college-educated officers, has the effect of diluting and eroding some of the more negative features of the monolithic police culture, such as conservatism, sexism and racism.

Reiner’s isolation of some of the main characteristics of police culture has also become a standard means of understanding the term including the following primary attributes: a sense of mission; suspicion; cynicism; isolation/solidarity; conservatism; machismo and pragmatism. There is also a common desire – on the part of younger officers – for action in the face of routine mundane duties. Cultures are complex ensembles of values, attitudes, symbols, rules, recipes and practices, which emerge as people respond in various meaningful ways to their predicament as constituted by the network of relations they find themselves in, which are in turn formed by different more macroscopic levels of structured action and institutions (Reiner, 2010:116- 132).

As illustrated in Bayley’s (1994) research police forces around the world share distinctive common experiences and characteristics. And while police culture may vary from place to place and change over time, Reiner suggests that a distinctive culture emerges in modern liberal, capitalist democracies where police face similar basic pressures. Skolnick also observes that culture has certain ‘universal stable and lasting features’ (2008:35).

2.4.1 Discretion.

Since in-depth studies began in the 1960’s and 70’s criminologists have insisted that police culture is central to understanding how discretion is used. There is consensus across the literature that the use of discretion by largely unsupervised street cops is seen as a major influencing factor in shaping the pattern of deviance. ‘The lower ranks of the (police) service control their own work situation and such control may well shield highly questionable practices’ (Holdaway, 1979:12).

The use of discretion has been a fundamental principle of policing since Robert Peel’s New Police first began patrolling the streets of London in 1829. The first formal public police were met with intense hostility, suspicion and resistance from across the social divide (Ignatieff, 1979). In order to be effective the police had first to convince the public to accept the code of criminal behaviour and their legitimacy. Discretion was the key to achieving this cultural shift by negotiating a complex, unofficial fluid ‘contract’ where the police defined activities they would turn a blind eye to, and those which they would not (Ignatieff, 1979: 33).

Robert Reiner (2010) observes that the use of discretion and minimal force, which has characterized consensual policing ever since, is done so for ‘principled and pragmatic reasons’ to gain the public’s trust and co-operation. Although the use of discretion can be problematical ‘it is inevitable and necessary, if only for pragmatic reasons of the limited capacity of the criminal justice system’ (2010:19).

Discretion is also necessary as it lubricates the criminal justice system and ensures that justice is discharged. If, as the gate keepers to the criminal justice system, police did not exercise discretion at street level then every misdemeanour would result in prosecution and the criminal law would be seen as overbearing, hugely costly and impracticable. The use of discretion is therefore essential to the fair enforcement of the law (Zedner, 2004:130).

It is therefore inevitable that police discretion is one of the most contentious issues in the criminal process. The principle of discretion rests on the choice to decide what action to take in a given situation; or the decision to take no action at all. Unlike any other organization discretionary power is located primarily with the lowest-ranking employees (McLaughlin & Muncie, 2013). The rank-and-file officer on the street decides if someone is to be treated as ‘criminal’ or ‘innocent’ with all the potentially life-altering consequences that flow from that decision for the individual concerned.

‘In other words, anything that might be inclined to influence behavior by frontline officers, such as deference to class or beliefs about certain ethnic groups being involved in crime, can create, construct and influence important and fundamental questions about how crime is defined and counted, and who is criminalised’ (Westmarland, 2008: 255).

The recognition that the police do not adhere mechanistically to the rule of law also raised the prospect of discrimination and malpractice. Given the dispersed character of routine police work, which gave it low visibility, discretion was hard to regulate. Various enquiries and reports into the police handling of public disorders and criminal investigations in the UK showed that police discretion was not an equal opportunity phenomenon. It disguised the disproportionate use of police power against certain powerless minorities – ‘police property’ – who were over policed and under-protected (Newburn & Reiner, 2007:915). The most negative manifestation of the use of discretion within a cop culture is to enable misconduct and more serious corruption. This behavior – ‘bent for job’ or ‘noble cause’ corruption – is protected behind a ‘blue wall of silence’ or ‘blue code’ where officers are reluctant to report wrong-doing by colleagues (Morton, 1993:207 – 213).

2.5 Occupational culture in An Garda Siochana.

The issue of an undefined, unofficial occupational culture within An Garda Siochana was thrust into the political and media discourse on policing after a number of unprecedented controversies engulfed the justice sector in 2013 – 2014. The so-called Whistle-blower scandal, which related to the abuse of the penalty points system and allegations of corruption in the Cavan/Monaghan Division, sparked a veritable bush fire which quickly spread, creating one of the biggest crisis to befall law enforcement in the history of the State. It culminated in the sacking of the Garda Confidential Recipient, Oliver Connolly in February 2014 (Irish Times, February 2014) and the resignations of the Garda Commissioner Martin Callinan in March 2014 (RTE, March 2014) and, in May 2014, that of the Minister for Justice Alan Shatter (BBC, May 2014).

The flames of controversy also engulfed the Department of Justice forcing the transfer of the Secretary General of the Department, Brian Purcell in July 2014 (RTE, July 2014). The combined controversies led to a succession of Government-appointed commissions of investigation and reports on various aspects of police accountability and behavior. Following decades of resistance the controversies finally pushed the Government to establish the Policing Authority on December 30, 2015, under the provisions of An Garda Síochána (Policing Authority and Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 2015.

The most dramatic evidence of the existence of a corrosive unofficial culture within An Garda Siochana was revealed by the Morris Tribunal which was established by the government to investigate misconduct, negligence and corruption in the Donegal Garda Division. It was a scandal of ‘unparalleled scale, which threatened its [gardai] legitimacy and internal morale’ (Conway, 2014:1). The Tribunal, which began hearing evidence in June 2002, spent 686 days in evidence, spread over six years, scrutinising the conduct, operation and organisation of the Irish police force.

Its origins lay with the garda investigation of the death of a man called Richie Barron in a hit-and-run accident in 1996. Among the matters investigated was the framing of two men for a murder that never occurred; false arrests and confessions forced from prisoners; the orchestration of false bomb finds and the planting of guns and drugs to secure convictions. In a separate case two of the officers at the centre of the investigation were found to have framed a Donegal night club owner for drug dealing which was later certified as a miscarriage of justice (Conway, 2010; 2014: Brady, 2014).

While up to this point in time there had been a dearth of information regarding the internal workings of the gardai, the Morris Tribunal was ‘one of the longest and most thorough inquiries into any police force in modern times’ (Brady, 2014:239). The tribunal produced eight reports containing devastating findings of systemic malpractice, corruption, abuse of power, disregard for procedure, negligent management and supervision, internal bullying, poor promotions and a belief on the part of the offenders that they could do so with impunity. Morris concluded that it was unlikely that such a culture was confined within the boundaries of just one garda division and debunked a ‘rotten apple’ defence by pointing to the complicity of management.

‘The sorry sequence of events … is an appalling reflection on the standards of integrity, efficiency, management, discipline and trust between the various members and ranks of the Garda Síochána … Gardaí looked to protect their own interests. The truth was to be buried. The public interest was of no concern’ (Morris Tribunal Report I/3.179, cited by Conway, 2014:190)

Conway (2014) has argued that the inherent disregard for the law and widespread breeches of the garda code of conduct exposed by the Morris enquiry reflected the negative conditions of a cop culture. Conway (2014b) expressed the view that the negative elements of the embedded values and norms of cop culture can be found in An Garda Siochana. But while she argued that this culture was one of the three core areas requiring to be targeted in a root-and-branch reform, she reflected the amorphousness of the concept through her inability to present a coherent methodology for so doing.

‘That is difficult, challenging work as this culture is transmitted on a daily basis across police stations and across generations. It takes courageous and dedicated leadership and an acceptance by police of a different outlook on the same job. While many practical changes (such as training, promotions, oversight and governance) can all contribute to changing culture we cannot legislate for a new police culture. This requires a continuous process stemming primarily from strong leadership’ (Presentation by Dr Vicky Conway at consultation seminar on justice reform, Farmleigh House, June 20, 2014.)

In November 2015 the Garda Inspectorate attempted to bridge the gap in research of police culture in Ireland when it published a comprehensive review, Changing Policing in Ireland, in which all aspects of the administration and operation of the Garda Siochana, including structure, organisation, staffing and deployment were assessed. In order to better understand the internal perceptions of garda culture, the Inspectorate conducted qualitative research through focus group workshops and structured interviews with staff at all ranks and grades. This was the first time that such research in this area was conducted within An Garda Siochana. The review acknowledged that ‘there is little available research in relation to garda culture in Ireland’ (Garda Inspectorate Report, 2015: 10).

Positive aspects of culture were described as a ‘can do’ attitude, ‘a sense of duty’, ‘a culture of service’ and ‘a good organisation at heart’. However, the research participants highlighted that the Garda Síochána is an organisation that can’t say no to requests and ‘tries to be all things to all people’. Negative comments on culture were described as ‘insular’, ‘defensive’, ‘not encouraging initiative’, ‘personal loyalty as opposed to organisational loyalty’, ‘a gulf between gardaí and senior managers’, and one where ‘garda staff and some junior ranks do not feel valued’.

Interviewees also spoke of a blame and risk-averse culture, whereby officers were afraid of the repercussions of making mistakes. As a result, more senior management could be concerned with ‘self-preservation’ rather than acting in the best needs of the organisation. Supervisors highlighted how some members were less inclined to engage with the public on the basis that ‘the less interaction, the less confrontation, the better’ (Garda Inspectorate Report, 2015:10–11). The report concluded that the official stated culture of the organisation was not displayed in the ‘real working culture’.

‘…it would appear that the culture as set out in official garda documents is not clearly exhibited in the real working culture. The perceptions noted in previous pages of this part suggest that the Garda Síochána does not support the stated culture fully through structures, performance measurement, operational decisions and priorities nor is it consistently displayed in the way policing services are delivered’ (Garda Inspectorate Report, 2015:177).

Rank-and-file gardai and their immediate supervisory ranks on the frontline have repeatedly highlighted the levels of aggression and conflict they have experienced while enforcing court orders and injunctions against anti-water charge protesters. They have complained of being the victims of a deliberate and sustained level of confrontation and harassment both physically and via social media (Lally, 2015). (For examples of the type of confrontations go to:

https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=water+protests

Reactions to these confrontations were reflected in a survey of morale organised by the Association of Garda Sergeants and Inspectors (AGSI) in December 2015. The survey was carried out over a 10 day period with a 27 per cent response rate from the 1,928 sergeants and inspectors. It found that 86 per cent of respondents felt that morale was either ‘low or very low’ (AGSI Morale Survey, 2015).

Cultural indicators included a sense of being under-valued by garda management with no support mechanisms in place to deal with issues of stress and under-resourcing.

‘There is a gulf, a gaping chasm between Management in HQ and the cold face of policing. Lack of support for people on the ground, lack of clear guidance and support around water protests and demonizing of Gardai on social media. There is a lack of support and lack of nurturing and wanting to get the best out of the Gardai on the front line. Mostly there is a complete lack of respect’ (AGSI Morale Survey, Section VI, Members commentary, December 2015).

2.6 Conclusion.

The theoretical framework assessed in this review illustrates how police culture is a constantly evolving, organic phenomenon, occurring naturally when a relatively small group of people are tasked with working in a volatile, confrontational and unpredictable environment. It was not until the 1950’s that the police became the subject of sociological scientific research following the path breaking Anglo-American studies of Michael Banton and William Westley who opened the way to a new world of policing scholarship. The review also highlighted how the concept of a monolithic culture has been replaced by a complex network of occupational cultures and sub-cultures. Officers working on the streets are moulded by their interactions with the public and peers which in turn influences how they exercise their discretion. The existing Irish literature also indicates the existence of the same variables in the occupational culture of An Garda Siochana.

Chapter Three

3. Methodology

3.1 Introduction.

This chapter outlines and then explains the research design and methodology employed in this study. It will discuss the rationale for the research topic and explain the process by which the data was collected, coded and then analysed. The chapter will also address the process of sample selection and access, the ethical issues involved, the possible contributions and limitations of the study.

3.2 Aims and Objectives, Research Question.

The main aim of this study is to explore the impact of conflict and confrontation on individual gardai working on the frontline through the lens of their individual lived experiences; and whether the responses are absorbed into the wider occupational culture of An Garda Siochana when considered in the context of the existing theoretical framework.

This was achieved by analysing the data to isolate any similarities or conflations which might suggest a uniform group response capable of being interpreted as a wider cultural response.

The objective of the research is to provide a starting point for further research of police culture in Ireland which, despite being existential to the discourse regarding garda reform, remains uncharted territory.

3.2.1 Issues addressed by the research.

The research question was sourced from the wider literature and used to explore how the individual experiences of confrontation impacts on the shape and form of the garda’s working personality. The individual responses of the research participants were then analysed for the purpose of identifying possible common themes contained in the prevailing literature on police culture.

3.3 Research Design.

The nature of the topic and research questions determined that an exploratory study be carried out utilising a qualitative approach to data collection, using the format of semi-structured interviews which allowed the interviewees greater flexibility and scope to express their lived experiences (Silverman, 2011) and which are expressed in words to reflect feelings, opinions, descriptions and anecdotes (Walliman, 2011). Qualitative data is expressed in words collected by asking/interviewing/observing (May,2001:121) as opposed to a quantitative approach which requires a more complex methodology.

The qualitative approach uncovers perceptions, attitudes, understandings and meaning in what is presented (Burnett, 2009). The use of an interview to obtain data is a ‘very good way of accessing people’s perceptions, meanings, definitions of situations and constructions of reality’ (Punch, 2009:168) while Greenhalgh (2001) describes qualitative research as being interpretative and concerned with interpreting and understanding phenomena through the meanings that people attach to them.

May (2001) states the importance of the design of interview questions is to construct them unambiguously and be clear in their mind what the purpose of the question is, and who it is for, and how the interviewee is intended to interpret it. By using semi-structured interview methods the researcher asked specific questions and was able to seek both clarification and elaboration on the answers given.

The semi-structured interview was chosen as it was assessed by the researcher as being the most effective for this particular study, providing a balance between the standardisation of a structured interview and the variability of the unstructured interview, thus allowing for greater flexibility and a natural flow. The research design was such as to encourage the interviewee to answer questions on their own terms by expressing their views and experiences, and to elaborate further on a topic if they wish (Bell, 1999). The aim was to encourage the interviewees to talk freely and thus avoid normative, ‘official line’ answers (Rubin & Rubin, 2005) while the questions were ‘carefully thought through so as not to restrict or predetermine the responses but at the same time cover the research concerns’ (2005:135). This allowed the researcher to then pursue further topics that arose with follow up, probing questions.

The dual exigencies of the time available to complete the study, including the time-consuming process of conducting interviews and transcribing the data; and the required size of the dissertation, dictated that the research participant group was based on a small purposive sample of eight serving front line gardai serving in the Dublin Metropolitan Region (DMR). The sample group was evenly divided in terms of rank – sergeants and gardai; geographic location – northern and southern divisions; gender and front line regular units.

3.3.1 Reflective note.

As previously mentioned in Chapter Two, police occupational culture and subcultures are generally invoked by academics as condemnatory rather than explanatory; it is often portrayed as a ‘pervasive, malign and potent’ influence on contemporary policing, particularly in the lower ranks and their use of extensive discretionary powers (Waddington, 1999). More recent analysis has described this as a convenient label which many commentators use yet do not explain or explore in any great depth (Chan, 1996; Westmarland, 2008) The literature also shows that the confrontational nature of police work is a key factor underpinning police occupational culture and that it lies in the early experiences of young officers on patrol (Skolnick, 1966; Reiner, 2010).

With this in mind the researcher was initially concerned that the research participants, who had been selected with the co-operation of the garda authorities, would fall back on a default defensive position of closing ranks and resorting to official line answers. However, all the participants involved demonstrated a willingness to share their experiences and in the process volunteering refreshingly candid views concerning their working environment and its impact on their cognitive perceptions.

None of the sample group were known to the researcher although the participants were all familiar with the researcher which was an aid in quickly establishing rapport. This interaction produced rich data from which to isolate common themes.

3.4 Access, Data sample and Data collection process.

3.4.1 Access.

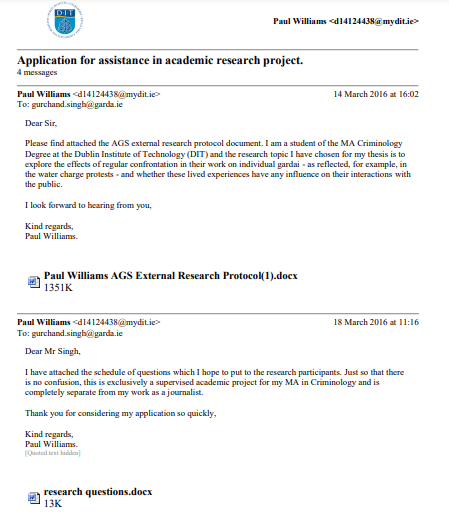

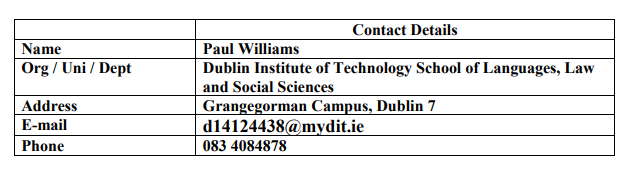

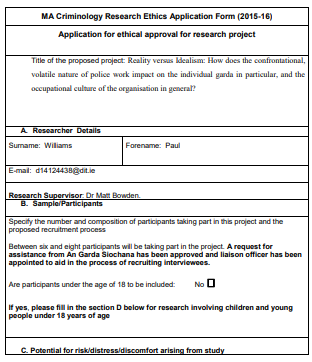

On March 14, 2016 the researcher requested clearance and assistance in gaining access to the sample group from the Garda Research Unit in Templemore through initial contact with the analysis service at Garda headquarters in the Phoenix Park (Appendix A) attaching the An Garda Síochána Protocol for External Research request form (Appendix B). The schedule of proposed questions for the research were also emailed on March 18 (Appendix C). On the same date assistance and clearance was confirmed. On April 18 the researcher was contacted by a member of the Research Unit in Templemore and provided with contact details for two designated liaison officers in the Northern and Southern garda divisions. The gate keepers then canvassed their colleagues for potential volunteers within their respective divisions. The research participants were selected from the list by the gate keepers who then provided individual contact details to the researcher.

3.4.2 Data sample.

A sample group of eight frontline officers were selected by the gate keepers which was, as requested, divided evenly between ranks, gender, and geographical location – Northern and Southern Divisions. The location was included to explore its relevance as a potential variable in the research data. The participants were operating in three distinct frontline units: regular shift (three members); Divisional Task Force which had been re-named Burglary Response Units (BRU’s) (three members); community policing (two members).

The length of service of the sample group ranged from seven years to 39 years divided as follows: 7 years, 8 years, 9 years, 10 years, 17 years (two officers), 20 years and 39 years.

The sample group was then coded by rank; numerical order in the interview schedule according to rank; gender and division. Therefore G 1 F N denotes: Garda rank; the first garda interviewed in her division; gender; and Northern Division. S 2 M S denotes: Sergeant; second male interviewed in his division; gender and Southern Division.

3.4.3 Data collection.

The process of data collection took place between May and August 2016 and the interviews were conducted in the garda stations where the participants worked. The interviewees had received the schedule of questions in advance of the interview and all of them agreed to have the interviews recorded. On average each interview lasted for an hour – none of the interviews took less than that time – and were recorded on the researcher’s iPhone 6.

Each interview began with the schedule of questions but the researcher found that the interviewees quickly branched out to discuss several aspects of their working culture which invariably led to supplemental questions regarding more specific areas.

The data was later transferred to a password-protected lap top computer. The interviews were then transcribed with each one requiring an average of six hours to complete in order to ensure the accuracy of the content transcribed.

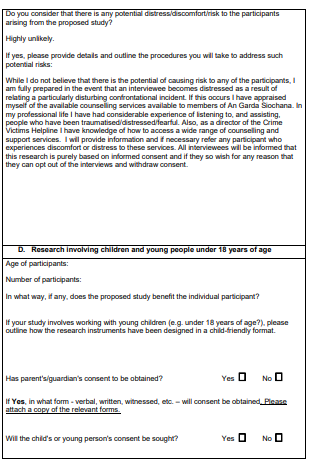

3.5 Ethical issues.

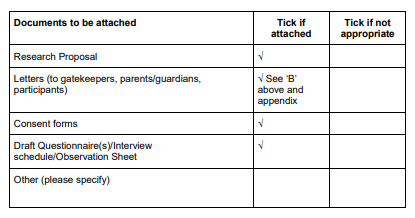

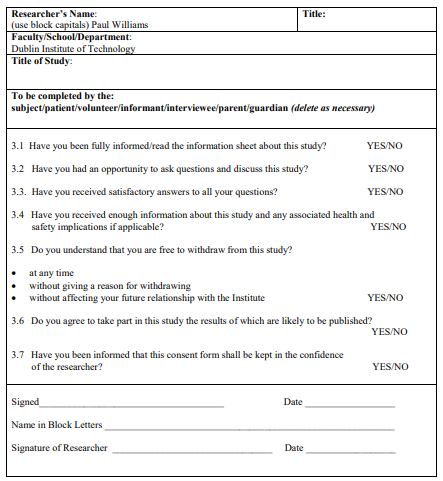

In April 2016 ethical approval was granted by Dr Kevin Lalor, the Head of School and Languages, Law and Social Sciences, Dublin Institute of Technology after receiving a Research Ethics Application form from the researcher (Appendix D). The researcher was also guided by the code of ethics adopted by the British Criminological Society.3

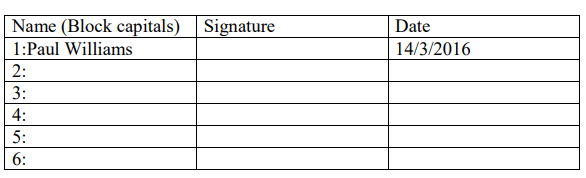

Having gained access to the sample group, the interview process took place between May and August 2016. All interviews were predicated on informed consent with each participant presented with an information sheet which clearly outlined the purpose of the research, the methodology being used, and assurances regarding ethics and confidentiality (Appendix E). At the conclusion of each interview the participant signed a consent form (Appendix F).

As a journalist working in the field of crime for many years the researcher was acutely aware of the importance of guaranteeing confidentiality and anonymity to the survey participants. To this end it was emphasised to each one that this was not a journalistic exercise but research for the preparation of a dissertation as part of the MA Criminology course in DIT. The interviews were deleted following transcription and the data was anonymised.

3 ‘Researchers should recognise that they have a responsibility to minimise personal harm to research participants by ensuring that the potential physical, psychological, discomfort or stress to individuals participating in research is minimised by participation in the research. No list of harms can be exhaustive but harms may include: physical harms: including injury, illness, pain; psychological harms: including feelings of worthlessness, distress, guilt anger or fear-related, for example, the disclosure of sensitive or embarrassing information, or learning about a genetic possibility of developing an untreatable disease; devaluation of personal worth: including being humiliated, manipulated or in other ways treated disrespectfully or unjustly. (British Society of Criminology, 2015, section 4i)

3.6 Data analysis.

A thematic approach was utilised in the research analysis without limiting the analysis solely to themes because it is argued that it provides a flexible and useful tool when applied (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Thematic analysis has been described as highly inductive and allows the analysis process develop ecologically with additional themes and points of reference emerging from earlier themes (Dawson, 2012). Rubin and Rubin (1995) claim that thematic analysis allows the researcher discover new concepts embedded throughout the interviews conducted.

A thematic approach was utilised in the research analysis without limiting the analysis solely to themes because it is argued that it provides a flexible and useful tool when applied (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Thematic analysis has been described as highly inductive and allows the analysis process develop ecologically with additional themes and points of reference emerging from earlier themes (Dawson, 2012). Rubin and Rubin (1995) claim that thematic analysis allows the researcher discover new concepts embedded throughout the interviews conducted.

An integrated approach was utilised in order to combine both emerging and predetermined codes. As this rinsing process continued the researcher could distil down the data, discarding the material that was not relevant and highlighting the material that was. The findings from the data were then considered against the existing literature in this area to establish common themes.

3.7 Contribution of the Study.

The fact that research in this particular area of policing has been practically non-existent in Ireland supports the view that any meaningful study will contribute to a greater understanding of policing. A constant theme among academics has been the reluctance of garda HQ to engage with external researchers. However, in the context of the lack of research this study may prove useful as a starting point for further research into the culture of An Garda Siochana.

3.8 Limitations of the study.

The fact that this research is based on a small purposive sample inevitably means that the findings are neither comprehensive nor definitive. The research question also concerns one narrow aspect of an area that is extremely broad, multifaceted and complex.

3.9 Conclusion.

This chapter has given a detailed account of the research methodology, including the rationale for employing a qualitative approach to data collection, using the format of semi-structured interviews, as the most effective way of achieving the aims and objectives of the study. It also highlighted: how the sample group was selected and access to the group was achieved; how the data collection process was undertaken; the ethical issues involved alongside the limitations and possible contribution of the study.

Chapter Four

4. Research Findings

4.1 Introduction and key themes.

This chapter covers the salient findings gleaned from the research project. As already adverted to above, the research produced a rich, multi-layered seam of data from eight hours of taped interviews and over 160 pages of dialogue transcript. When the data were analysed several common themes emerged from the individual responses of the participants which conflate with the characteristics of police occupational culture as defined in the existing theoretical framework.

Through the lens of the individual lived experiences of the participants, the semi-structured methodological approach made it possible to identify distinctive cognitive responses in the sample group which Skolnick (1966: 2008) characterises as the ‘working personality’ of the officer on the beat working in a uniquely dangerous and volatile environment. In order to achieve a clearer comparative analysis the primary themes in the data have been integrated with the theoretical literature. While the themes are isolated and dealt with individually there were several thematic cross-overs and intersections which become apparent as the chapter is read. The themes identified and discussed in this chapter are: confrontation; social isolation/internal solidarity; cynicism; suspiciousness; discretion; cynicism; canteen culture; and action. The chapter ends with a conclusion which summarises the main findings.

4.2 Confrontation.

The confrontational nature of modern police work is one of the factors underpinning police culture which lies in the early experiences of ‘rookies’ on patrol and the influence of peers and mentors (Skolnick, 1966; Reiner 2010). Each member of the sample group could recall with clarity the first occasion when they were involved in a threatening or violent situation. In each instance the officers were young recruits with the majority experiencing a confrontational and potentially dangerous incident – normally an assault or threat of assault – in a very short period of time after graduating from Templemore; ranging from between a few weeks and a few months.

A common thread running through the testimonies of the participants was that the original incidents presented as defining moments in their working lives with regard to how it impacted on their working personalities and the development of what Skolnick calls a ‘perceptual shorthand’ for dealing with situations on the ground. Some of the females within the sample group reported how they had found the initial incident upsetting: two of the four officers were assaulted; one was threatened in an armed robbery and the fourth witnessed a colleague being seriously injured in an assault.

Alternatively none of the male respondents said they had been traumatised or upset by similar experiences. However, this reaction should also be considered within the theoretical context that ‘machismo’ is an important ingredient of police culture with males tending to be more reticent about expressing fear/trauma. A number of the male gardai interviewed also referred to the fact that their physical size may have mitigated the effects of their original encounter with violence and confrontation.

One of the male gardai (G1MS) described how his first confrontational experience had been exciting (see paragraph 4.9). However, the same officer revealed that of his earliest experiences on the job, the most challenging and disconcerting experiences were investigating the discovery of dead bodies.

A male sergeant (S4MS) with 17 years’ experience made a similar comparison between confrontation and other duties.

‘Listen, when you have a few years’ service in this job, confrontation is the easiest part of the job. It’s the other things that you cannot be, in any way shape or form, be prepared for … rape victims, cutting down dead bodies, coming across particularly bad things … I’ve lost people who I’ve trained with, been at the scene of those things … confrontation is easy, when you compare them to the emotional toll, confrontation is a piece of piss’ (S4MS).

GIFN was assigned to her first station two weeks when she and her mentor were attacked by a group of men as they tried to seize neglected horses in north Dublin.

‘So after that incident I was aware of my limitations … I was going to check horses, it was very simple and within minutes I was grabbed by the throat by a traveller…(now) when I go to every call, Control gives me the gist of what the call is but I’ll never assume that’s the call I’m going into.’ (G1FN).

S1FS is a supervisory sergeant with 17 years’ service attached to a regular unit in the Southern Division. Four months after graduating from Templemore she was punched in the face while making her first ever arrest, that of a male drunk driver. She suffered a badly swollen eye which necessitated her taking time off work to recover. And while she described suffering a total of four ‘bad assaults’ on duty in her career to date, she said the first had the greatest impact.

‘Overall did it have a long term effect on me? No, but it taught me a very valuable lesson in relation to policing. Don’t ever take your eye off a prisoner for one second. And people are capable of doing anything … That was a really good lesson very, very early on and that was the big lesson that I learnt in relation to that’ (S1FS).

G2MN was in-situ three months in the Northern Division when he and two colleagues were attacked by a group of 15 youths whilst trying to affect an arrest. Even after ten years’ service he could still recall feeling how the few minutes it had taken for assistance to arrive was ‘like an hour or two’.

He estimated that he experiences confrontational or threatening situations ‘at least once every six months’ and has developed a cognitive shorthand for dealing with such unpredictable events.

‘It’s strange really. It (conflict) nearly develops into your personality and the way you weigh up the personalities of people you are working with, and you’ll weigh up all these certain scenarios to try and avoid issues, as we call them in Garda speak, kicking off’ (G2MN).

4.3 Social Isolation/Internal Solidarity.

Zedner (2004) argues that the distinctive characteristics of cop culture derive from the fact that police work closely together, in dangerous, unpredictable situations and often in conflict with the surrounding community. This engenders an institutionalized sense of isolation and an ‘us-and-them’ attitude to the world outside the police station. It is rooted in a shared knowledge system containing strongly-held beliefs about the nature of policing and those they police.

Skolnick (1966) identified three inter-connecting themes within police occupational culture that result from being continually occupied with potential violence and conflict: social isolation, internal solidarity and suspiciousness. Social isolation emerges in response to a unique combination of two principal variables of the police role – danger and authority. It is a product of the unsociable nature of the job and wariness of authority, therefore solidarity and social isolation are mutually reinforcing.

The research participants unanimously expressed the view that working with the public and being in a position to provide social service and protection was a source of job satisfaction. However, a number of themes emerged which support the concept of social isolation. In particular the interviewees expressed strong views that the courts deal leniently with people who assault gardai which, they felt, reflected a wider societal opinion that police officers should accept violence as an inherent consequence of their work. In addition they also complained of a lack of support and empathy from their management when they have been assaulted or have experienced particularly traumatic events.

G1FN spoke of a particular individual living in the district where she works who had accumulated 30 convictions for assaulting and threatening gardai ‘but he hasn’t been in prison for it.’ She also described her experience after being punched in the face while trying to break up a fight outside a nightclub.

‘…I’m injured just get on with it. I still had to try and pull them apart until my partner came over. I got assistance and ended up arresting them and brought them back. But nothing ended up happening to them for punching me in the face … it’s seen like part of your job, being abused verbally but sometimes physically. It’s just seen as part of the job … I’ve been punched, I’ve been kicked, I’ve been spat at and nothing’s happened. And it’s a serious offence but I don’t think it’s acknowledged as a serious offence through the organisation, through the public … I was in court one day and I remember I witnessed a member giving evidence and part of his evidence was that the accused verbally abused him … And the judge said well you should be a bit thick skinned and that was the judge’s response … So I think it seems that verbal abuse and physical abuse to a certain point is part of the job. I don’t think you get the support from higher ranks that you should get’ (G1FN).

S1FS described violent confrontation as an increasingly regular feature of frontline policing which, in her opinion, appeared to have become more acceptable to society.

‘In my opinion it’s increasing. There is not a month that goes by here that a guard isn’t assaulted in some form or another and that’s just in one district … It seems to be more the norm and it doesn’t shock anybody when a guard is assaulted…’ (S1FS).

The research participants also reported encountering hostility from the public the nature of which varied depending on social class and geographical location. And while the data revealed that gardai expect as the norm, a degree of hostility in most working class areas, the participants said that they enjoyed a better relationship with working class communities than in more affluent, middleclass neighborhoods.

S1FS was unequivocal when asked to nominate the social cohort she least liked to work with:

‘More affluent areas, from my own personal point of view, they’re more difficult to police, they’re more difficult to work with, you get more calls and the crime calls would be reduced, and the social aspect or whatever way you would phrase that, that’s increased. So you would say that 80% has got to do with social stuff or stuff that guards have nothing got to do with it and 20% would be crime’ (S1FS).

She was then invited to nominate which social grouping she preferred to work with.

‘Working class, one hundred percent. One hundred percent! Yes, there would be more confrontation and you have more serious things to investigate but I do believe that we are appreciated more and what we do is appreciated more’ (S1FS).

The same sentiment was echoed by G1MS who began his career assigned to a station in a more affluent area of south Dublin.

‘Like from starting off in Rathfarnham you’re kind of looked upon, not by all but a lot of them, as their own kind of personal security you know … You’d be going to calls and people would be looking at you as if you know nothing, you’re only a guard and you’re here for us … I remember a chap called once to the hatch and his son’s thousand odd euro bike had been stolen from a shop in the village and he was very upset by this, as you would be, it’s a grand you know, a lot of money. And he said there would be a lot of CCTV and I said, grand perfect. He said when are we going up to view it and I said you won’t be going to view it, it will be me viewing it but I’ll do it whenever I’m next in the car so. Oh what do you mean? I said you can see I’m here on my own, you can see there’s no one else here with me. I just can’t close the station to go up and get your bike, you know. This wasn’t at all satisfactory to him and why wasn’t I doing it quicker and stuff. And I was kind of standing there taking it for a while and then I got a bit pissed off and said I know you’re a bit upset but if your son hadn’t left a thousand euro bike unlocked outside a shop it probably wouldn’t have been stolen. And who was I to say this and who was my supervisor and I told him the details and said, look I’ll investigate it but that’s life. It wasn’t locked. It’s not my fault, it’s not your fault but it’s your son’s fault and the person who stole it’ (G1MS).

G2FS described how some of her colleagues were seriously assaulted when they responded to a disturbance at a house party in what she described as a ‘quiet, middle class area’ of the south city.

‘We responded to a house party in a good area and naively went there thinking this will be fine because this is a grand area and they’re probably about 12. And it turned out to be a lot more serious than that and we got turned on in the house and trapped in the house and one of my colleagues was badly assaulted and I wasn’t assaulted but a lot of my colleagues were … and then we looked for assistance and we got it pretty quickly, thank God, so what seemed like a long time wasn’t a long time at all and then our backup arrived and they were dispersed pretty quickly … It was a quiet road quiet, typical suburban cul de sac and that is what I think probably shocked us more than anything. Obviously there are certain areas that you would go into that you would be exercising more caution because you would be expecting a certain type of person where in this place we were expecting it to be more low key’ (G2FS).

G2FS also noted that the suspects for the assault, which left one colleague with a slashed face requiring 20 stitches, were subsequently acquitted. She pointed out how they had hired a well-known and experienced barrister to defend them.

4.3.1 Internal Solidarity.

As mentioned above social isolation and internal solidarity are mutually reinforcing as a consequence of work demands and occupational pressures; the unsociable nature of the work and the perception of the prospect of unpredictable danger in the course of routine encounters with the public on the street (Skolnick, 1966; Chan, 1997; Manning, 2007; Reiner, 2010). The bond of solidarity is seen to be functional to the survival of officers in such a dangerous environment and that it ‘offers its members reassurance that the other officers will “pull their weight” in police work, that they will defend, back up and assist their colleagues when confronted with external threats, and that they will maintain secrecy in the face of external investigations’ (Goldsmith, 1990: 93-94).